By Kyle Jaros

The boom of big cities across China in recent years reflects not only market forces unleashed by reform and liberalization but also renewed—and, in some cases, intensified—state intervention in the economy. Policymakers in some provinces have effectively turned a long-standing policy of “strictly controlling the size of large cities”1 on its head, promoting the build-up of their top metropolitan centers as a key part of their economic strategies. State-led efforts to transform Xi’an, the sleepy capital of Shaanxi province, into an “international metropolis” and regional “growth pole” epitomize this larger trend.

Xi’an’s experience over the past decade shows both the potential and the perils of China’s state-led urban development.2 Strong support from the Shaanxi provincial government and various central government agencies has helped to fuel explosive economic, physical, and population growth in the city since the early 2000s. Between 2000 and 2011, Xi’an’s GDP surged from 69 billion yuan to 366 billion yuan, its built-up area expanded from 187 square kilometers to 343 square kilometers, and its urban population grew from 2.86 million to 3.91 million.3 But top-down interventions have also affected the character of Xi’an’s urban growth. While prioritizing Xi’an’s function as a regional economic engine and showcase, higher-level policymakers have been less attentive to the internal coherence of urban development. And provincial efforts to orchestrate metropolitan development from above have set off fierce turf battles between different government tiers and actors. Even as higher-level interventions enable rapid development in Xi’an, they may compound urban ills such as sprawl, redundant construction, and fragmentation of governance.

Of course, national and regional governments have good reasons for supporting the development of their leading cities.4 A growing chorus of academics and policy experts has championed the productivity and competitiveness advantages of large cities. Especially for policymakers in stagnant or late-developing economies, building up the largest urban centers may offer a shortcut for achieving economic internationalization and industrial upgrading. In recent decades, national and regional governments around the world have taken measures to enhance the competitiveness of the Londons and Bangalores that link them to the global economy and house leading industrial sectors.5

Of course, national and regional governments have good reasons for supporting the development of their leading cities.4 A growing chorus of academics and policy experts has championed the productivity and competitiveness advantages of large cities. Especially for policymakers in stagnant or late-developing economies, building up the largest urban centers may offer a shortcut for achieving economic internationalization and industrial upgrading. In recent decades, national and regional governments around the world have taken measures to enhance the competitiveness of the Londons and Bangalores that link them to the global economy and house leading industrial sectors.5

While China’s metropolitan turn in development policy has come relatively late, it has also been unusually forceful. China’s provincial governments and central bureaucrats have powerful administrative means for steering development in space, including control over financial and fiscal resources, land-use quotas, preferential policies, and major infrastructure and industrial projects. Since the early 2000s, provincial governments across China as well as central state agencies such as the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) have targeted policy support and state resources to build up major metropolitan areas that can thrive in a more open and competitive economy and drive the development of broader regions.6

But pro-metropolitan development strategies in China’s provinces aim to harness big cities as much as to empower them, and top-down interventions may clash with urban interests even as they boost metropolitan growth. Provincial governments seek to bulk up their leading metropolitan areas as regional economic engines and fiscal cash cows, and they invest heavily in building up metropolitan infrastructure and industry. Viewing major cities as economic assets, however, higher-level policymakers may neglect the internal quality and coherence of urban growth. Higher-level government actors also grow jealous of the fiscal and administrative clout amassed by booming cities. Provincial and central policymakers tend to favor approaches to metropolitan development that strengthen cities economically while simultaneously expanding higher-level influence over urban development.7 Rather than embracing the urban character and organization of top cities, top-down metropolitan development strategies work around it, forging outwardly competitive metropolitan areas rather than internally vibrant cities. Shaanxi’s efforts to boost Greater Xi’an’s size and economic profile embody these two sides of state-led urban development—both the power of higher-level actors to drive urban growth, and also the ways in which top-down efforts can distort development.

Shaanxi’s extended crisis of economic competitiveness has created a strong impetus for metropolitan development. Located far inland, Shaanxi has long remained one of China’s poorer provinces. Though Shaanxi served as an important base for state-owned industry after the Communist takeover, it has struggled to adapt to more competitive economic conditions since the 1980s. Entering the twenty-first century, Shaanxi’s economy was buoyed by rapid energy-sector development and by a new national-level Open the West Campaign, but the province’s urban and industrial development remained anemic.8 Industrial reforms in Xi’an progressed slowly, and the city lagged behind inland rivals like Chengdu and Wuhan when it came to market size and the quality of investment climate. By the early 2000s, provincial elites perceived an urgent need to make Shaanxi’s core urban areas more competitive.9

In response to such concerns, Shaanxi’s government has launched a series of increasingly bold initiatives to build a stronger Xi’an metropolitan region and a “core growth pole” for its provincial economy. In 2002, provincial leaders announced a long-term strategy of economically and physically integrating Xi’an with the nearby city of Xianyang, and called for fostering a broader belt of high technology industry around Xi’an.10 Between 2004–2005, provincial leaders stepped up their support for Xi’an’s economic development through the approval of new development zones and the rollout of stronger industry- promotion policies.11 A more aggressive provincial strategy took shape following the 2007 arrival of Zhao Leji as Shaanxi’s Communist Party chief. Zhao, a rising star in the Party establishment, signaled that building a larger, more competitive Xi’an metropolis would be a top priority, and called for devoting more provincial policy support and investment to what was already by far the largest, wealthiest city in the province.12 The new leadership also set about obtaining special policies from Beijing for development of the Guanzhong economic region around Xi’an.13 Negotiations with Beijing paid off as the State Council in 2009 designated the broader Guanzhong region as a special economic area and approved plans to accelerate Xi’an-Xianyang integration and build Greater Xi’an into a 10 million-person “international metropolis.”14 This state-level recognition gave Shaanxi and Xi’an greater access to central resources as well as expanded scope for launching subnational policy initiatives.

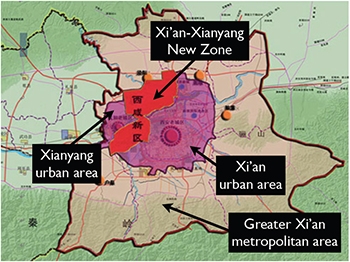

At the center of Shaanxi’s efforts to promote faster metropolitan development under these new central policies has been the creation of a mammoth Xi’an-Xianyang New Zone. In the months after it received central endorsement for plans to build an integrated Xi’an-Xianyang “international metropolis,” Shaanxi’s leadership took advantage of its new policy mandate by marking out a 560 square-kilometer special development area along the Xi’an-Xianyang border.15 Lying within municipal boundaries but administered by the provincial government,16 the New Zone is intended to serve as the physical platform for Xi’an-Xianyang integration and as home to several of the new industrial and urban districts that will help constitute the Xi’an international metropolis.17 In the near term, New Zone construction is meant to facilitate quick economic and administrative breakthroughs. Long stymied by city-level resistance to economic and physical integration, provincial policymakers are using construction of new infrastructure and urban districts in the New Zone to stitch Xi’an and Xianyang together into a contiguous urban entity of larger size and higher profile. And, given the political difficulty and undesirability (from Shaanxi’s standpoint) of having Xianyang absorbed into Xi’an administratively, construction of a provincially managed New Zone gives the provincial government a way to achieve its goal of enhancing Xi’an’s size and profile while also asserting greater control over metropolitan development.18 To jumpstart development in the zone, Shaanxi has invested several billion yuan of start-up capital for infrastructure, made available enormous tracts of land, extended a sweeping array of preferential policies to investors, and kicked off several major investment projects in the zone.19

If construction of the Xi’an-Xianyang New Zone makes clear the power of higher-level actors in China to drive urban development, however, it is also symptomatic of the ways in which top-down interventions can distort urban growth. Provincial officials see their efforts to establish new urban districts several miles from the established city centers of Xi’an and Xianyang as a means of deconcentrating urban growth, but they are in practice supporting scattered real estate and industry development in areas with limited transportation access and market demand.20 Local planners voice concerns that heavy construction amid the villages, flood plains, and ancient ruins between Xi’an and Xianyang will perpetuate Xi’an’s urban sprawl while eating away at some of the area’s richest farmland and most delicate environmental and cultural resources.21 Because Shaanxi’s vision for the New Zone conflicts with existing city-level plans for locating new industrial, commercial, and residential developments, New Zone construction has exacerbated local competition and duplication of investment across the metropolitan area.22

If construction of the Xi’an-Xianyang New Zone makes clear the power of higher-level actors in China to drive urban development, however, it is also symptomatic of the ways in which top-down interventions can distort urban growth. Provincial officials see their efforts to establish new urban districts several miles from the established city centers of Xi’an and Xianyang as a means of deconcentrating urban growth, but they are in practice supporting scattered real estate and industry development in areas with limited transportation access and market demand.20 Local planners voice concerns that heavy construction amid the villages, flood plains, and ancient ruins between Xi’an and Xianyang will perpetuate Xi’an’s urban sprawl while eating away at some of the area’s richest farmland and most delicate environmental and cultural resources.21 Because Shaanxi’s vision for the New Zone conflicts with existing city-level plans for locating new industrial, commercial, and residential developments, New Zone construction has exacerbated local competition and duplication of investment across the metropolitan area.22

Meanwhile, municipal officials, especially those from Xi’an, resent—and resist—attempts to expand provincial control over urban development matters.23 The resulting conflicts over physical and bureaucratic turf can make even routine urban governance matters highly political, as policymakers adopt measures designed to undermine policies by their counterparts at other levels. And, as the provincial government focuses state resources on the development of new metropolitan districts, it is implicitly diverting resources both from older, more densely populated urban districts in Xi’an and Xianyang and also from the smaller urban centers and impoverished rural areas that still make up the majority of Shaanxi province. This, in turn, may stimulate even more migration from peripheral areas into an already crowded, polluted, and underserviced capital city.

Pouring resources and policy support into Greater Xi’an, provincial authorities will doubtless succeed at increasing the city’s population and GDP. It is less clear, though, whether state-led urban development can create a real international metropolis—one with the broad, resilient economic base and well-knit urban fabric to attract people and firms from around the globe.

Kyle Jaros is a Sidney R. Knafel Dissertation Completion Fellow, Samuel P. Huntington Doctoral Dissertation Fellow, and Graduate Student Associate of the Center. He is also a PhD Candidate in the Department of Government. His research examines the political economy of regional and urban development in China.

Kyle Jaros is a Sidney R. Knafel Dissertation Completion Fellow, Samuel P. Huntington Doctoral Dissertation Fellow, and Graduate Student Associate of the Center. He is also a PhD Candidate in the Department of Government. His research examines the political economy of regional and urban development in China.

Photo Captions

- Xi’an’s Rapid Growth: GDP and Builtup Area, 2000–2012. Data source: China Data Online. http://chinadataonline.org.

- State-led Urban Development: The Xi’an- Xianyang New Zone. Map image source: Website of Xianyang City http://www. xianyang.gov.cn. Labels by the author.

Notes

- “City Planning Law of the People’s Republic of China, December 1989.” (English translation). Accessed at www.china.org. cn/english/environment/34354.htm.

- Scott (1998), among other scholars, has explored the widespread tendency for state-led development interventions to misfire and/or generate unintended consequences. See Scott, James C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- China Data Online. http://chinadataonline.org.

- See for example, Krugman, Paul. 1991, “Increasing Returns and Economic Geography.” Journal of Political Economy 99, no. 3; Glaeser, Edward L. 2011. Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier. New York: Penguin Press.; McKinsey Global Institute. 2009. “Preparing for China’s Urban Billion.” McKinsey Global Institute. www.mckinsey.com/ insights.

- For a discussion of metropolitan-oriented policy interventions, see Brenner, Neil. 2003. “‘Glocalization’ as a State Spatial Strategy: Urban Entrepreneurialism and the New Politics of Uneven Development in Western Europe.” In Peck and Yeung (eds.), Remaking the Global Economy: Economic-geographical Perspectives. London: SAGE.; Park, Bae-Gyoon, Richard Child Hill, and Asato Saito. (eds.) 2012. Locating Neoliberalism in East Asia: Neoliberalizing Spaces in Developmental States. Studies in Urban and Social Change. Oxford; Wiley-Blackwell.

- Xu, Jiang. 2008. “Governing City-Regions in China: Theoretical Issues and Perspectives for Regional Strategic Planning.” The Town Planning Review 79, no. 2/3: 157–185.; Ke, Shanzi, and Edward Feser. 2010. “Count on the Growth Pole Strategy for Regional Economic Growth? Spread-Backwash Effects in Greater Central China.” Regional Studies 44, no. 9.1131–1147.

- Xu (2008); Interview with provincial policy advisor, Xi’an, China, July 2013.

- Vermeer, Eduard B. 2004. “Shaanxi: Building a Future on State Support.” China Quarterly. 178: 400–425.

- Chengshi shangquan. August 16, 2002. “Menghui chang’an you duoyuan [Chang’an remains a distant dream].”August 16, 2002. www. cnki.com.cn.

- Shaanxi Provincial Government (2002). “Zhonggong shanxi sheng wei shanxi renmin zhengfu guanyu ‘yi xian liang dai’ jianshe shixian guanzhong shuaixian kuayue fazhan de yijian. [Shaanxi Provincial Party Committee and Shaanxi People’s Government Opinion Regarding ‘One Line, Two Belts’ Construction]” Provincial government document obtained in Xi’an, December, 2012.; Jingji guancha bao. February 3, 2012. “Xianyang zheng zai xiaoshi? [Is Xianyang disappearing?]” www.cnki.com.cn.

- Xi’an ribao. October 1, 2004. “Jia zhibang zai wo shi jiancha gongzuo shi qiangdiao quanli zhichi cujin Xi’an zuo da zuo qiang chongfen fahui zhizheng daidong fushe zuoyong [During his inspection work, Jia Zhibang stresses the need to fully support and push forward efforts to build up Xi’an].” www.cnki.com.cn.

- Zhao Leji. 2007. “Guanzhong jingji qu fazhan jige zhongda wenti de yanjiu [Research on several major problems in the development of the Guanzhong economic area].” Document obtained in Xi’an, December 2011.

- Shaanxi ribao. August 5, 2008. “Shenyi bing yuanze tongguo ‘guanzhong chengshi qun jianshe guihua’… [Government reviews and approves in principle ‘Guanzhong city group construction plan’ …]” www.cnki.com.cn.; Jingji Guancha Bao. July 3, 2009. “Guojia gei xi’an yi kuai ling pai [The central state gives Xi’an a token of authority].” www.cnki.com.cn.

- National Development and Reform Commission. 2009. “Guanzhong-tianshui jingji qu fazhan guihua [Guanzhong-Tianshui Economic Area Development Plan].” www.sdpc.gov.cn.

- Shaanxi Provincial Government (2009). Shaanxi ribao. November 25, 2009. “Xixian xinqu zhengshi qibu jiang cheng da xi’an hexin qu [Xi-Xian New Zone formally launches, set to become core area for Greater Xi’an].” www.cnki.com.cn.; Shaanxi Provincial Government. 2009. “Shaanxi sheng renmin zhengfu guanyu yinfa xixian xinqu guihua jianshe fang’an de tongzhi [Shaanxi Province People’s Government Circular Regarding Printing a Xi-xian New Area Plan Construction Scheme]” www.shaanxijs.gov.cn.

- The province took full control over New Zone administration in 2011, whereas between 2009–2011, municipal authorities retained more administrative control over the zone. Jingji guancha bao. (2012 ).

- Shaanxi ribao (2009); Shaanxi Provincial Government (2009).

- Interview with provincial policy advisor, Xi’an, China, June 2012.

- 21 shiji jingji baodao. June 14, 2011. “Xi-xian xin qu shi nian po ti [10 years of the Xi-Xian New Zone]” www.cnki.com.cn.; Xi’an Wanbao. March 6, 2012. “Zhan linkong jingji guili [The charm of opening up an airport economy]” www.cnki.com.cn.

- Author’s interview with foreign investor, Xi’an, China, March 2012.

- Interview with local academic, Xi’an, China, March 2012.

- One particularly conspicuous example of this is the Xi’an municipal government’s continued efforts to develop a huge Weibei Industrial Zone to the northeast of the city that would try to attract some of the same kinds of developments the New Zone is competing for. Interview with provincial policy advisor, Xi’an, China, July 2013.

- Interview with provincial enterprise executive, Xi’an, China, February 2012.